Africa’s forests have reached a worrying turning point. A new study shows that many forests now release more carbon dioxide than they take in. This change is mainly due to deforestation and forest degradation. It is the first time in modern records that Africa’s forests have become a net carbon source instead of a natural buffer against global warming.

The research, published in Scientific Reports, was led by scientists from the National Centre for Earth Observation at the Universities of Leicester, Sheffield, and Edinburgh. Using satellite data, they tracked changes in forest biomass over time. Their findings are crucial for global climate goals, which is especially true for the targets set in the Paris Agreement.

A Major Shift After 2010

The study shows that Africa’s forest carbon balance changed around 2010. Between 2007 and 2010, forests were still gaining carbon, acting as a natural sink. But from 2010 to 2017, the continent lost roughly 106 million tonnes of forest biomass each year. Converted to carbon dioxide, this equals about 200 million tonnes of CO₂ emissions annually.

This is significant because Africa is home to the second-largest block of tropical rainforest, mainly in the Congo Basin. These forests store carbon, regulate rainfall, and support biodiversity. Losing their ability to absorb carbon means the world must reduce emissions faster elsewhere.

The trend comes from two main causes: deforestation, which is when forests are cleared, and forest degradation. In degradation, forests stay, but they lose biomass from selective logging, fires, or mining. These processes reduce the amount of carbon stored in vegetation.

Hotspots of Concern: DRC, Madagascar, and West Africa

Central Africa, Madagascar, and parts of West Africa show the most pronounced changes. The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) holds more than half of the Congo Basin rainforest. In 2024, it lost a record 590,000 hectares of primary forest. This is the largest loss in its monitoring history.

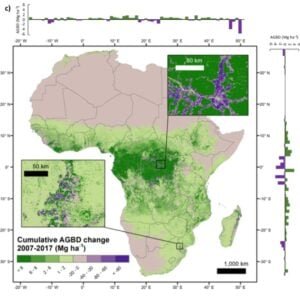

The map below shows changes in Aboveground Biomass Density (AGBD) from 2007 to 2017. Green areas represent gains, while purple areas indicate losses.

The upper-right inset shows biomass loss due to deforestation near settlements, rivers, and roads in the DRC. The lower-left inset features a South African forest plantation, highlighting clearcuts next to newly planted areas.

The main pressures come from small-scale farming. Rural communities clear forests for crops. Artisanal mining has also grown because of global demand for minerals like cobalt, copper, and gold.

Madagascar faces deforestation from slash-and-burn farming, charcoal production, and commercial logging. In West Africa, countries like Ghana, the Ivory Coast, and Nigeria are losing forests due to agriculture and timber extraction. Together, these regions contribute most of the 200 million tonnes of CO₂ now released by Africa’s forests annually.

Global Context: How Africa Compares

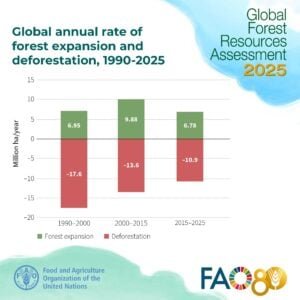

Worldwide, forests remain under pressure. Between 2015 and 2025, the world lost about 10.9 million hectares of forest annually, down from 17.6 million hectares per year in 1990–2000.

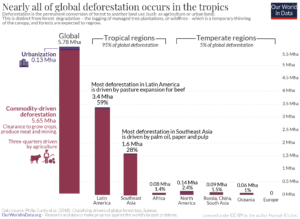

In 2024, the world lost 6.7 million hectares of primary forest. This loss was caused by fires, logging, agriculture, and land clearing. Notably, fires have recently overtaken agriculture as the main cause of tropical forest loss.

Within this global picture, Africa has the highest rate of net forest loss among all regions during 2010–2020. This aligns with the new study showing that Africa’s forests have shifted from being carbon sinks to carbon sources.

South America, with the Amazon, still loses a lot of forest, but slower now. Meanwhile, some Asian countries have gained forest areas in recent years.

This contrast reveals a troubling trend. While some areas reduce forest loss, tropical forests in Africa and parts of South America are under serious pressure. This situation endangers ecosystems and jeopardizes global climate efforts.

Why Forest Biomass Is Falling

Several factors explain Africa’s forest losses:

- Expanding agricultural land

- Timber harvesting, legal and illegal

- Mining and mineral extraction

- Charcoal and fuelwood production

- Population growth and land pressure

Even partial forest losses across large areas add up to significant carbon emissions. Climate change also weakens forests: higher temperatures, droughts, and more frequent fires slow regrowth and reduce forest health.

Implications for Climate Targets

Africa’s weakening forest sink has serious global implications. Forests in Africa, Asia, and South America currently absorb much of the world’s emissions. If Africa’s forests stop absorbing carbon and start releasing it, the global carbon budget tightens.

Professor Heiko Balzter, senior author of the study, notes:

“If we are losing the tropical forests as one of the means of mitigating climate change, then we basically have to reduce our emissions of greenhouse gases from fossil fuel burning even faster to get to near-zero emissions.”

National climate strategies also face more pressure, as many countries rely on forests to meet their climate pledges.

COP30 and Funding Efforts: Are They Enough?

The study was released after COP30 in Brazil, where countries discussed new funding for forest protection. The Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF) launched with $5.5–$6.6 billion. It will pay tropical countries about $4 per hectare to keep their forests. At least 20% of funds will go to Indigenous Peoples and local communities who play a major role in forest protection.

Forest carbon financing is picking up speed. Global investment in sustainable forest management, restoration, and conservation almost doubled from 2020 to 2024. It grew from under US$12 billion a year to about US$23.5 billion annually.

This surge comes from a mix of public funds, which make up about 60% of total flows, and growing private capital. Private capital’s share increased from about 25% in 2020 to around 40% in 2024.

- MUST READ: Forest Finance Hits Record Growth in 2025: Investment Doubles for Nature-Based Climate Action

More companies are aiming for net-zero emissions. As demand rises for verified forest carbon credits, forests are seen as both ecological assets and investment opportunities.

However, experts note that the funding is far below what is needed. Brazil had proposed $125 billion to protect and restore tropical forests globally. Africa’s fast-changing ecosystems make this gap even more urgent.

The Congo Basin: A Carbon Giant Under Pressure

The Congo Basin absorbs about 600 million tonnes of CO₂ each year. This helps balance emissions from other continents. But its capacity is declining due to increasing forest disturbance.

If the trend continues, the world could lose one of its last major natural carbon buffers. Protecting this region is vital for Africa and the world’s climate. It impacts biodiversity and rainfall patterns well beyond the continent.

Reversing the Trend: Can Africa Save Its Forests?

Reversing the trend is still possible but requires strong action. Protecting remaining forests is the most urgent step. Governments should reduce pressure from agriculture and mining. They also need to improve land-use planning and monitor illegal logging.

Funding mechanisms like TFFF can help, but must increase to match the scale of the problem. Local communities and Indigenous groups, who manage large forest areas, need financial and technical support. Restoring degraded forests can help recover some carbon storage, but it takes time.

Africa’s forests shifting from absorbing to emitting carbon is a major warning for the planet. It shows how fast natural systems can change under pressure. This highlights the need for stronger global cooperation, better funding for forest protection, and support for local communities.

If action is delayed, the world will face an even harder path to meet climate goals. With stronger investment and protection measures, however, forests can continue storing carbon, supporting biodiversity, and sustaining millions of people across Africa.

The post Africa’s Forests Are Now Emitting Carbon Instead of Absorbing It appeared first on Carbon Credits.