This is Part One of a two part series.

In this first feature, we look at pyrolysis basics, the benefits of biochar in manure management and how two leading companies are addressing the main economic limitation. Stay tuned for Part Two in our September/October issue, where we’ll explore the exciting market potential for biochar, challenges to scaling up and what’s left to learn.

“It will not be easy, and there is a lot of hard work to be done, but biochar as an agricultural input is poised for rapid growth, finally.”

Many would agree with this statement from the April 2025 newsletter of the U.S. Biochar Initiative, with biochar now poised to make major impact. And one of its raw feedstocks is manure.

Biochar is a unique material that results from pyrolysis, a high-temperature process which acts on carbon-rich raw organic substances in a low-oxygen environment. Methane-rich gas and bio-oil are also produced, which can both be used to make heat, electricity, gaseous fuel and more. Biochar characteristics depend on the feedstock, but also the pyrolysis temperature (typically between 660ºF to 1,650ºF) and how long the feedstock is in the reactor.

Feedstock materials range from wood, crop debris and manure to biodigester digestate, human sewage biosolids and food processing by-products – anything with lots of carbon will do. Compared to the raw version of these feedstocks, the biochar form offers many superior characteristics. With manure biochar for example, there’s little odor compared to raw manure. In handling and storage, compared to any raw material, biochar is porous, generally lighter in weight (with a density of only 5-12 lbs/ft2) and stable (it does not readily decompose).

Because of its composition and porosity, it can also bind with various materials. For example, University of Nebraska-Lincoln scientists have found that biochar added to the soil in the pens at beef feedlot operations absorbs significant amounts of nitrogen, preventing some loss of that nutrient to the environment. (However, note that during pyrolysis, over half of the nitrogen in raw materials can be lost to volatization.)

Manure biochar

Solid-liquid separation is already common in dairy and swine production for many good reasons. The solids can be used for bedding or applied to the fields, and due to their low weight, they’re more easily transported to areas far from the farm. But as Joseph Sanford at University of Wisconsin-Platteville has noted, converting solids to biochar can further reduce their mass by up to 80 percent.

Unlike nitrogen, no phosphorus is lost in pyrolysis. In fact, manure biochar can have a P density six times that of the original manure. This mineral also remains stable in manure biochar in a form that’s better that other forms for crop absorption. Therefore, adding manure biochar to fields is much better in comparison to raw manure in terms of runoff of excess P (and N) into waterways.

The carbon in biochar of any kind is also very stable, although during pyrolysis, some of the carbon is lost to volatization, similarly to nitrogen, explains Jesper Knijnenburg at Khon Kaen University in Thailand, who with colleagues recently published an analysis of P dynamics in manure pyrolysis. The remaining carbon in the biochar, he says, becomes more stable through the formation of aromatic rings, a molecular structure resistant to bacterial decomposition, a process which results in CO2 emission. Thus, “some studies have demonstrated that the application of biochar to soils can have short-term effects,” adds Knijnenburg, “such as availability of nutrients and water retention, but also long-term effects such as increased soil organic carbon stocks.” A current study in Canada involves adding biochar to soil to aid in nutrient release management and reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

Manure biochar is also already added to feed and livestock bedding in some parts of the world. Mahmoud Sharara at North Caroline State University and his colleagues have found that adding biochar made from Miscanthus (a tall grass species) to poultry bedding successfully reduces ammonia emissions in the barn.

Detractions and cost

Though Knijnenburg and his colleagues conclude there are good prospects for retaining P in pyrolyzed manure, at the same time manure can contain significant levels of heavy metals. Like P, during pyrolysis these heavy metals are largely conserved and their concentrations generally increase with higher temperatures.

“Secondly, there are concerns about the toxicity of biochars,” they state. “Pyrolysis may result in the generation of volatile organic compounds and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons,” with concentrations of both “strongly dependent on the feedstock and pyrolysis conditions.” And, contrary to the stability of N and P in biochar, there’s a lot of potassium release from biochar, which may be more pronounced at pyrolysis temperatures.

Pyrolysis also comes, of course, with capital investment in the reactor and operational costs as well. And the feedstock must be quite dry. Sanford has found for manure pyrolysis to make economic sense, dry matter content should be at least 70 percent. Liquid manure generally has only one to seven percent dry matter, slurry eight to 12 percent and semi-solid manure 13 to 19 percent.

All such costs are offset by the value of biochar as an input and the potential energy value from the gas and biooil. There’s also potential, note Knijnenburg and his colleagues, to use manure biochar in water treatment and construction materials. At the same time, they find there is currently “very high variability and uncertainty” in estimating the cost and benefits. Knijnenburg concludes in any cost/benefit analysis, “drying requirements for wet manures represent a significant cost consideration.”

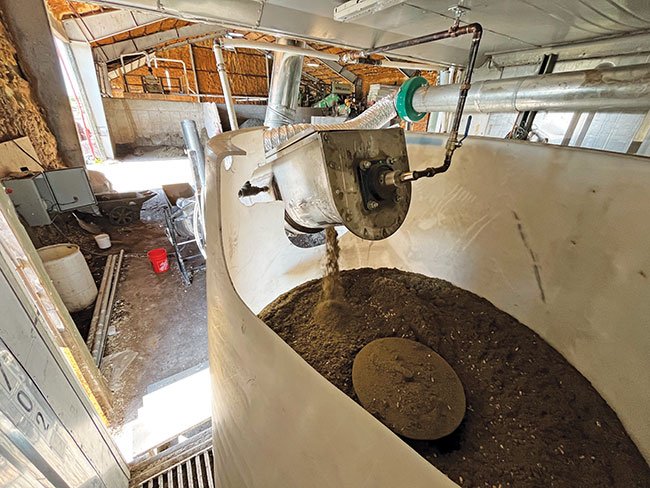

Dried manure being fed into the reactor as part of the Cornell project, which is currently undergoing intensive study by dairy tech consulting firm Newtrient.

Drying manure: Biomass controls

Among the world’s pyrolysis technology companies are several that are taking drying costs of manure head on.

One is Biomass Controls of Connecticut. Its team recently partnered with Cornell University in a project at a New York dairy farm, where “our system uses the gases from the process to provide the thermal energy to heat water that is used to dry the incoming manure,” explains Biomass Controls CEO Jeff Hallowell. He adds that this setup includes “a catalytic emissions technology that uses a thermochemical process to combust the gases after the pyrolysis of the separated manure.” Biomass Controls now has more than 25 other containerized pyrolysis systems of various sizes installed in the U.S., India and Africa, and all of them accept feedstock with more than 35 percent moisture. These include manure, human biosolids, algae and industrial food waste. Their largest unit can process up to eight tons of raw material per day.

This month (June 2025), the Cornell project is undergoing intensive study carried out by dairy tech consulting firm Newtrient. “We will look at durability of the equipment, ease of use, what moisture content of the manure solids is needed for effective system operation, and more,” explains Jeff Porter, the company’s technical consultant. Porter recently retired from the USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, where he served as the Leader of the National Animal Manure and Nutrient Management Team. “We will also compare the energy produced by the system through pyrolysis for manure solids,” says Porter, “versus anaerobic digestate.”

Frichs pyrolysis

Another pyrolysis technology firm capturing gas from the process is Frichs Pyrolysis in Denmark. This month (June 2025), its first full-scale reactor becomes operational on a pig farm, with an annual capacity of 10,000 tonnes of dry matter. Later this year, a similar reactor will be commissioned at the chicken and crop farm of the company’s founders Lars Bojsen and his son Peter. Over the years, the Bojsens have looked at various ways to manage the manure generated by their 150,000 laying hens, with the farm having only 370 acres of cropland (and in a European political climate where there’s substantial pressure to minimize the environmental impact of manure).

A few years ago, they connected with a local manufacturing firm to designed a ‘flash pyrolysis’ system where materials are heated to 800°C for only two to three seconds. Frichs Pyrolysis is now at the commercialization stage, with plans to build more reactors in Europe over the next year or so.

The raw chicken manure must be dried down from 25 percent dry matter to about 85 percent. The dried litter is pulverized in a hammermill to achieve a particle size of 3 mm or less, so that the reactor is receives a consistent raw material. Straw is also pulverized and added to the reactor. “With its much-higher dry matter content, straw doesn’t need to be dried down as much as manure,” explains chief commercial officer Bent Plougstrup. “You also produce more gas with straw included and we want make a lot of gas.”

As mentioned, some of that gas is used to dry the manure and some power the pyrolysis itself. The rest can be used for on-farm generators or be further scrubbed and enter the regional natural gas network. “Gas can be used in a variety of ways, whatever is needed or wanted, and you can also separate CO2 and methane,” says Plougstrup. “Another use is district heating or combined heat and power systems. Maybe you install a reactor near a water purification plant, where they can use the biochar, the heat and the power.”

Frichs Pyrolysis currently has two current research collaborations with scientists at the University of Southern Denmark. One is an investigation of using bacteria to combine hydrogen and reactor biogas to create CO2 and methane. The other is examining how adding hydrogen to the reactor biogas can achieve pure methane for the grid.

Drying costs

There are also other pyrolysis systems, reports Sanford, that have separate drying systems associated. “When we were working with one company, drying… was an additional fee,” he reports, “which was similar to the cost of manure biogas dryer. Additionally, most of the systems are designed for processing wood-based material where the moisture content can be much lower than manure, and so, some of these systems with dryers may still not be suitable for fresh manure solids without additional drying.”

Overall, Sanford cautions, “it’s important to understand what the system was designed to do. That said, farms that would be able to invest in this technology likely have drying capabilities already.” He concludes that while the manure drying aspect of pyrolysis is a limitation, “it is not an impossible hurdle to climb.”

Come back for Part Two, in which we’ll take a further look at manure pyrolysis economics and building the market for manure biochar. •