Hay crop yields have stagnated and part of the reason could be that more data is collected from other crops, such as corn, than for forages.

Everything that can be measured can be improved, was the main message of Jean-Philippe Laroche’s keynote speech during the 16th annual Canadian Forage and Grassland conference in Fredericton, N.B., on Nov. 19, 2025.

WHY IT MATTERS: Hay provides important feed for ruminants, but it competes against growing yields in others crop for acres in Canada.

While the concept can apply to all aspects of farming, Laroche was specifically talking about the opportunities producers have for overall forage production improvements. He’s an expert in dairy production, nutrition and forages with Lactanet.

“Without data to guide our decisions, it can be difficult to improve,” he said.

“Even today, the forage sector uses relatively few performance indicators, which limits progress compared to other areas of agricultural production.”

Using the example of dairy production, Laroche said Holstein productivity has improved over the past 70 years from less than 5,000 kilograms to almost 12,000 kg per year, per cow.

This productivity was driven in part by milk testing, genetics and nutrition, he said. Modern dairy cows were selectively bred by looking at the characteristics of the offspring of specific bulls and selecting the best examples.

“Over time, the herd became better producers and converted nutrition into milk more efficiently.”

The other piece of the puzzle was nutrition.

“By using multiple data such as the cow’s bodyweight, their productivity, and the nutritional value of feed, we are now able to implement precision nutrition. For example, by calculating amino acid requirements and supply.”

This is all done using data.

He said this level of analysis has not been the case for forage yield, at least in Quebec.

“Here, we have on average six tonnes of dry matter per hectare, and that’s been the case for at least 20 years,” he said. “The potential is much higher. We haven’t improved because producers aren’t measuring yield. In other crops such as soy, corn, and other grains, almost every producer knows their yield. And we do see improvements over the years. This is not a coincidence.”

He said the reality is, in 2018, it was estimated that in Quebec only 16 per cent of dairy producers knew the production cost of their forages. And that cost corresponds roughly to 25 per cent of the total costs to operate a dairy farm.

“If we want to improve the output, we need to measure more and use that data to drive improvement. We need to collect regional averages,” Laroche said.

The importance of collecting data is greater than ever as producers struggle to balance their books in the face of rising production costs.

“Better yields help dilute fixed costs,” he said.

Forage production costs saw an increase of 110 per cent over the past 18 years; corn silage saw a 75 per cent increase in cost, but yields have increased by 19 per cent.

“It’s a hard message, but we haven’t improved hay crop yield,” he said. “But we need to for profitability. We need to limit the increasing costs of capturing that crop.”

The good news, Laroche believes it can be done by collecting data related to forage yield, which in turn will highlight where producers have opportunity. At a minimum, he said most producers in Quebec could improve their forage production by one tonne per hectare, bringing yield from six tonnes to seven. In the south of the province, he said the yield could be more; upwards of 12 tonnes with good data and improvements.

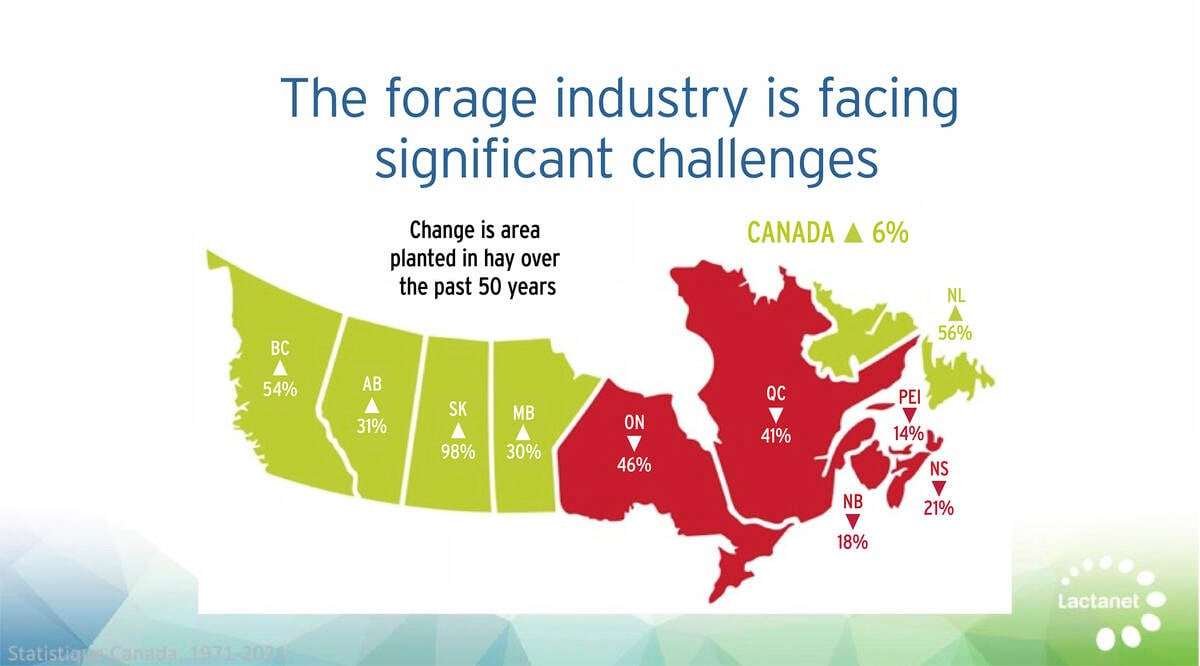

Laroche said improving the data on forage could reverse the trend where hay crops are decreasing, especially in Ontario and Quebec, where it’s decreased by 41 per cent over the past 50 years.

“In Quebec there is a decline in the number of cows due to higher productivity, so fewer cows are producing more milk,” he said. “Another reason is producers are replacing part of the hay crops with corn silage.

“There is a danger in this,” he said. “Too much corn can negatively impact profitability, especially when you look at the big picture – soil health, mycotoxins, etc.”

He said there is a perception that corn silage is cheaper, but he says when producers look at the big picture hay crops are worth more because of higher protein, fibre and improvements to the soil.

“Corn isn’t bad as a forage,” he said, “but there is an optimal balance.”

As an example, Laroche said farmers may use wheat straw as an added fibre with corn silage. This practice has its downside, as it could lead to more mycotoxins in the mix. Hay crops have other benefits.

“They provide nitrogen to the next crop, that’s why it’s important to look at the whole farm system,” he stressed.

By implementing crop rotation with hay, producers can also increase the yield of corn crops, improve soil health, which in turn improves drought tolerance.

“The solution is simply measuring our yields, because this leads to comparisons and improvement.”

Laroche outlined the steps he sees as necessary to measure performance beginning by raising awareness among producers and providing a simple data collection and compilation system. Once the data is collected and analyzed, it can be used to facilitate area planning, analysis of problematic fields, perform regional comparisons and calculate production costs.

All of this he said will lead to improvement.

The post Closing the forage gap: Why hay yields are falling behind appeared first on Farmtario.