Rotating cattle through paddocks with careful management is the best way to sequester carbon in soils, says a University of Guelph professor.

WHY IT MATTERS: There’s increasing interest among consumers and retailers in rotational grazing systems as an important part of soil health management.

Kim Schneider, an assistant professor in forage and service crops in the department of Plant Agriculture at the U of G, shared examples from Ontario field studies illustrating the benefits of grazing livestock as part of a sustainable soil management program.

She was one of the keynote speakers at this year’s 16th Annual Canadian Forage and Grassland Association conference held in Fredericton, N.B., in November.

Joining the conference virtually, Schneider presented some of the data collected over the past two years that looks at how integrating livestock impacts soil.

“Rotational grazing is the gold standard for carbon sequestering in soils,” she said.

Schneider said adaptive multi-paddock (AMP) grazing, where cattle rotated frequently through paddocks when the plants were in their optimal vegetative state, and allowed adequate rest periods for regeneration of pastures, has been shown to increase carbon sequestration.

“This decreases the carbon footprint of beef production for Ontario producers.”

Schneider pointed out below ground plant biomass is important to the formation of stable organic matter, or soil organic carbon. She said the research illustrates the importance of adding perennials to the equation as they tend to have more root mass, and for longer in the season, than annual crops. This helps contribute to the pool of stable carbon.

She described the study, which is based on work the research team started in 2021.

Looking at five locations, they studied 10 commercial beef farms, which were paired based on similar soils and climate.

“We had five paired farms to have a comparison of adaptive multi-paddock grazing and continuous or non-AMP grazing,” Schneider explained. “We tried to compare as many variables as possible, looking for similar soil types, and topography.”

Farms participating on the AMP grazing side had to have been rotationally grazed for at least 10 years to be included. The non-AMP fields were selected because they could support livestock for the season.

“They weren’t being fed supplementary hay, because we didn’t want that to interfere with the amount of carbon accumulating.”

Fifteen deep soil cores were collected on each of the properties.

“For the most part, we tried to go 60 centimetres,” Schneider described.

“Some of the pastures were on stony ground, but we were able to get to 45 centimetres on all our sites.”

Soil samples were segmented into 15 cm increments.

Soil health increased with more intensive grazing.

The results showed that soil organic carbon, total nitrogen, soil organic matter stability and PLFA (phospholipid fatty acids, which provides a snapshot of the soil microbial community) abundance increased under AMP grazing.

“We did find the higher soil organic carbon in the rotationally grazed systems. Still, I would emphasize overall, we had pretty high carbon in both systems,” she said.

As part of the study, the team sampled nearby annual crops and woodlots.

“Both pastures are higher than the annual crop,” she said. “But the AMP is not significantly different from the wood plot. If we’re trying to regenerate our soils and bring up the carbon levels, rotationally grazed pastures might be as high as we can get in an agricultural setting.”

Schneider said the studies are important because they provide Ontario data, which will help support regional programs such as OFCAF and other climate solution programs and answer the question of which practices are good for sequestering carbon.

Roots influenced stable carbon

The researchers also looked at mineral-associated carbon stock, which are thought to be more stable in the soil, and important to sequestering carbon. This was measured at two depths, zero to 15 cm and 15 to 30 cm.

“In the top zero to 15 centimetres where we do have the most roots, we did have higher mineral associated organic carbon, or organic matter,” she said. “There were more microbial groups in this soil.

“We found overall soil organic carbon, total nitrogen and soil organic matter stability with microbial abundance were increased under rotational management.”

She attributes that to great root mass in the AMP fields, because they roots aren’t getting stunted by overgrazing.

“We have a good amount of root biomass and then with more root biomass, we would get more root exudates. Microbes love to feed on root exudates, so we increase our microbial biomass. Ultimately, when the microbes die, they’re forming that stable or mineral associated soil organic matter.”

Creating a soil health test

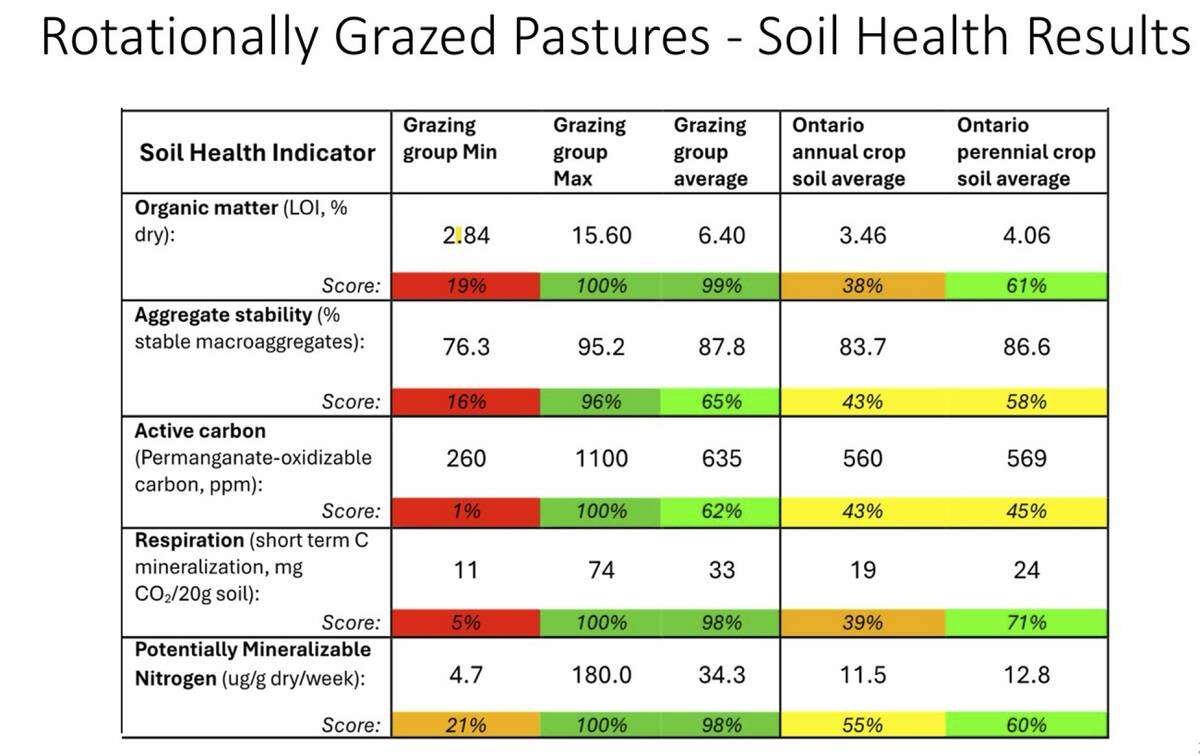

She said the research ties into a larger body of work started in 2018 when the province released the Ontario Soil Strategy and the goal to develop a soil health test. Experts came up with five soil health indicators including soil organic matter, soil respiration, active carbon, potentially mineralized nitrogen and aggregate stability.

“They basically came up with a soil health report by soil class.”

Schneider said results from an analysis of research were collected from 18 farms practicing rotational grazing with sheep, beef or dairy. Thirty-six samples (two per farm) were collected in 2024 and submitted for soil health analysis. These results were compared to Ontario annual crop soil averages and provincial perennial crop soil averages (from hay fields and pastures).

She explained out of the 36 samples, two were scoring in the red.

“Sometimes pastures are grown on land that isn’t top class, these were lower class lands, with shallow soil depth to bedrock, so those sites did score poorly.

“The averages of our grazing group were all higher than the perennial crop soil average, adding support that rotational grazing helps these soil health scores.”

Schneider added the data suggested the number of years a pasture was rotationally grazed also improved the results.

“After about 10 years, it gets less variable.”

She said the next phase of research is to look at what happens when livestock grazes annual crops and whether that impacts carbon sequestering. She points to winter wheat, which is typically harvested in July in Ontario.

“We have this window where we can plant a cover crop and graze it.”

Schneider said they’re now looking at whether that improves soil health and the yield of the following crop. They’re looking at seven sites and doing trials. Preliminary results don’t show a lot of change, and she’s hoping repeated grazing and manure distribution will make a difference in the long term, but they need to collect more data.

The post Researchers tie intensive grazing to improved soil health appeared first on Farmtario.