Does the future of food lie in a lab?

That question is no longer science fiction. It’s at the heart of cellular agriculture, a growing field that includes precision fermentation and cultivated meat that is being researched in many countries around the world.

WHY IT MATTERS: Cellular agriculture is seen by some as a solution to feeding the global population while reducing reliance on livestock production and other resources.

This includes Norway, a Scandinavian country strongly focused on sustainability and reducing resource use, where its largest food research institute, NOFIMA, is doing some of the most advanced work in the world in this field.

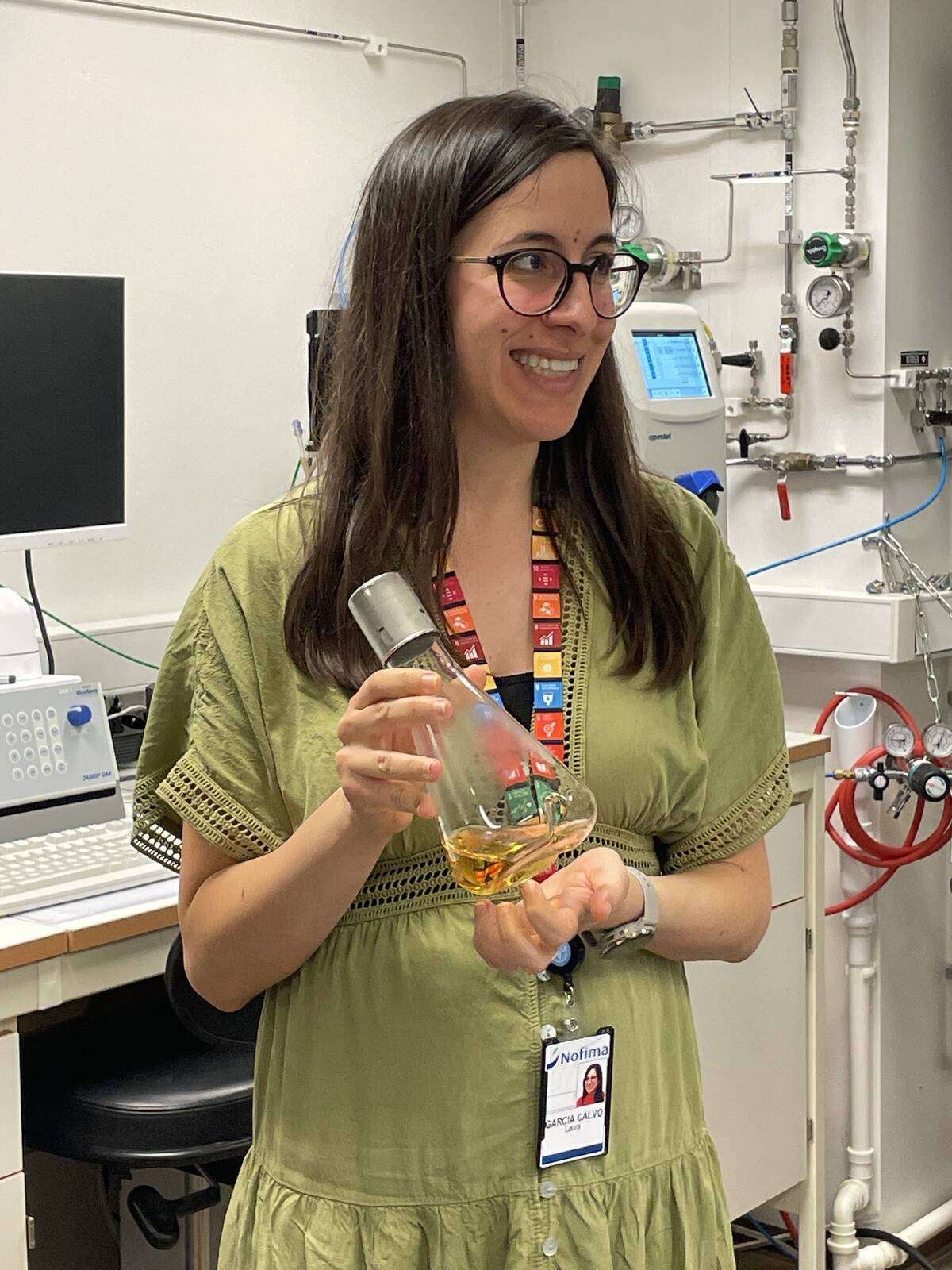

NOFIMA focuses on applied research that works closely with the agriculture and agri-food industry to “create value,” said Laura Garcia Calvo, a research scientist in microbiology at the institute.

“At the end of the day, the big question is how we are going to make enough food for 2050,” Calvo said, adding that the solutions involve using new technologies, just like agriculture once evolved from horses to tractors.

Cellular agriculture covers two main approaches, each designed to fill a different gap in the food system: precision fermentation and cultured meat.

Factories of fungi

Precision fermentation uses microorganisms such as yeast, fungi, or bacteria as tiny factories to produce very specific food ingredients. Scientists add a biological recipe into the microorganism so it produces proteins, fats, or other compounds, a process that is then refined before scale-up.

Ingredients that can be produced this way include dairy proteins such as whey and casein, egg proteins such as ovalbumin, collagen, fats, sweeteners, vitamins and even colourants.

Perfect Day is a company already selling milk proteins — essentially milk without the cow — in the United States. Together with Remilk from Israel, Perfect Day is now seeking regulatory approval in Europe.

NOFIMA’s work in the field includes developing new microbial strains, advanced bioprocess monitoring, and turning waste streams into valuable inputs — for example, converting dairy byproducts or leftover sugars from plant protein processing into new ingredients.

“This is very much part of the circular economy,” Garcia Calvo said.

Muscle media

Cultivated meat, sometimes called cultured meat, takes a different approach.

Instead of making individual ingredients, scientists grow actual animal muscle cells outside the animal — ultimately to make structured products like steak or unstructured meat like hamburger or chicken nuggets.

The science is complex, according to senior NOFIMA scientist Mona Pedersen.

Muscle cells require highly specific growth media, which are nutrients that tell the cells how to grow and specialize. Most existing media were designed for pharmaceutical use, not food, and many rely on animal-derived serum that is expensive and not suitable for large-scale food production.

“Upscaling is one of the biggest challenges,” Pedersen said. “We need to upscale a lot if this is going to reach a significant percent of the population.”

Denial or acceptance

Regulation and consumer acceptance are equally important hurdles. Singapore became the first country to approve cultivated meat for commercial sale in 2020. The U.S. followed in 2023, approving cultivated chicken from UPSIDE Foods and GOOD Meat.

Europe is still developing its regulatory framework, and European Union member Italy has banned cultivated animal-cell foods altogether.

Research suggests European consumers place high trust in regulatory approval, noted Pedersen, making clear rules critical to adoption.

“We need to develop consumer acceptance in parallel with the technology,” she said.

Advocates argue cellular agriculture could reduce land and water use, lower greenhouse gas emissions, improve food safety, and strengthen food security in regions with poor soils or limited growing conditions. A 2021 report by Ontario Genomics estimated the emerging sector could ultimately represent a $12.5-billion annual opportunity for Canada.

NOFIMA researchers see these technologies not as eliminating agriculture but rather about adding new tools to the system that could help make food production more resilient, efficient and future-ready.

Still, big questions remain and cultivated meat in particular has been struggling to gain traction and establish profitability.

Will these products replace traditional farming or simply supplement it? Who owns the technology? Where will the energy, water, and feedstocks for microorganisms come from? And will consumers choose to eat food grown this way?

The post How microbiologists are making protein without the farm appeared first on Farmtario.