Researchers and practitioners came together in early February to explore how real-time, digital replicas of the planet could change the ways we anticipate risks and test solutions to environmental change.

Hosted by the European Space Agency (ESA), the ESA Digital Twin Earth Components: Open Science Meeting 2026 focused on showcasing and advancing the next-generation of these so-called “digital twins.”

Freya Muir, research coordinator for Future Earth and ESA, attended the workshop to help connect these technical developments with broader sustainability needs. In this Q&A, she unpacks what “digital twins” of the Earth are, how they build on Earth observation data, and why they are becoming an increasingly important tool for science-backed decision-making in a rapidly changing world.

Future Earth: What is a “digital twin”?

Freya Muir: As the name suggests, it is a replica or reproduction of an object or system in digital form, stored as data in computer software. In the context of Earth science, a digital twin of the Earth would be a copy of all the complex, diverse environments and interacting processes that make up life on our planet. The key part that makes a digital Earth twin different from just an image or dataset, is the flow of information in real time. Extremely up-to-date observations are repeatedly gathered about the system and used to create and continuously fine-tune this digital model.

How does it use Earth observation data

Digital twins are used to predict, stress-test, and understand the different environmental interactions happening around us. What sets them apart from traditional Earth system models is three things: real-time data and the short-term, operational design of the simulations being run; the integration of human activity, economics, and policy changes into the simulations; and agile and flexible designs where new observations continuously fill gaps.

Similar to weather forecasts, huge amounts of information are gathered about the environment from different sensors, and fed into complex physics equations, which simulate how the system will evolve over the coming minutes, hours, and days. Earth observation plays an important role in this real-time aspect, offering very regular and repeatable insights about a variety of metrics across almost the entire globe. Now, what if we had the same kind of weather forecasts, but for air pollution events in cities? For coastal erosion from an incoming storm? For glacial floods in remote mountain settlements? We can explore these kinds of processes and impacts with digital twins informed by Earth observations.

How does Future Earth contribute to this work with ESA?

The partnership between Future Earth and ESA is bringing use cases for digital twinning to the focus of the data providers. The analyses, modelling, and workshopping performed by Future Earth’s Global Research Networks lays the groundwork for building digital twins of Earth. We need to understand how these systems operate and how the parts fit together before we can run the simulated machine regularly. Satellite data also helps in these exploratory activities, illuminating the past histories of the atmosphere, ice sheets, oceans, and the biosphere.

ESA also funds a number of Future Earth research projects that capture the digital twin essence, the most recent of which are geared towards climate change and cities. Researchers from low- and middle-income countries are making use of free satellite data to build decision support systems for air quality improvements in Delhi, and early warning systems for flooding across smallholdings in Ethiopia.

The user-focused design of these twins links strongly with Future Earth’s science-policy activities, as the results and what-if tests can guide decision-making towards more resilient and sustainable societies.

Who can benefit from these digital twins, and in what ways?

By capitalising on the hundreds of terabytes of Earth observation data generated every day (much of which is publicly available), stakeholders and decision-makers can get unparalleled insights about the environmental risks they and their communities might be facing.

Using digital twins’ flexibility over space and time, national governments can understand climate change impacts on food and water security; energy providers can plan out reliable and resilient renewable infrastructure; and local authorities can roll out more targeted disaster responses and mitigation actions.

Were any real-world examples shared that show how digital twins can anticipate risks or test solutions?

The European Commission has launched Destination Earth as a flagship initiative to monitor and simulate natural phenomena across the globe. ESA’s Digital Twin Earth programme contributes to this with funding and satellite-based resources for groups working on focused parts of the Earth system, such as forests, ice sheets, and rivers. The aim is to eventually fit these components together in an operational, interconnected framework where, for example, simulated warming in an ocean component can be incorporated into simulations of ice sheet melt.

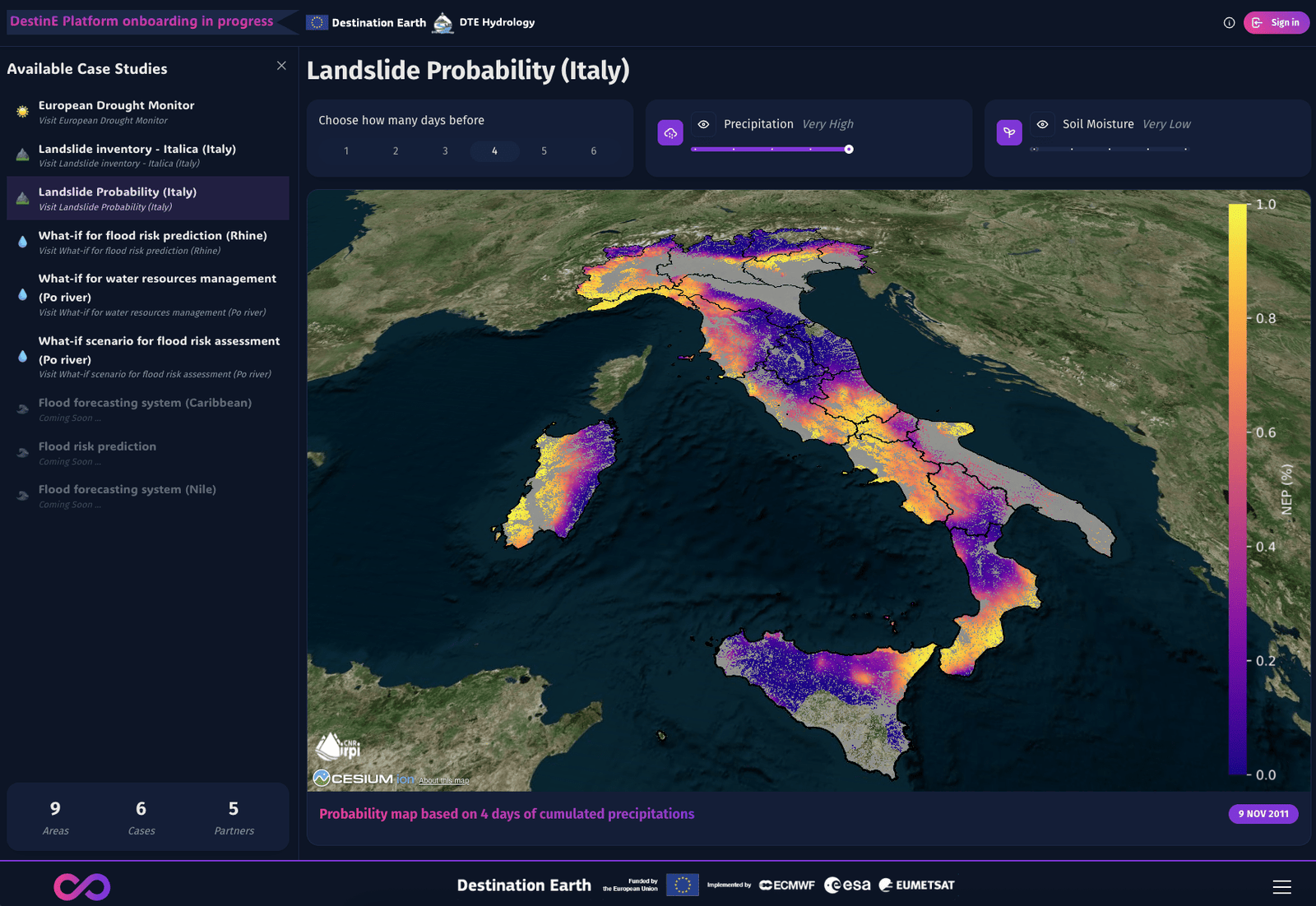

The workshop was a chance for ESA-supported teams and interested parties to share their experiences in developing environmental digital twins. The lead projects showcased their data-driven dashboards and predictions: DTE Hydrology demonstrated their what-if scenarios for flood risk across Italy; EOAgriTwin painted a colourful picture of agricultural stressors; and Forest DTC showed how fires, pest infestations, and plantation management all influence present and future carbon stocks.

What challenges does the technology still face?

Because of the sheer volume of data being processed and modelled at Earth system scales, machine learning is being used for satellite data processing, future predictions, and relationship analysis in digital twin workflows. This has revolutionised computational efficiency in these simulations, because we’re utilising shortcuts and letting the data speak for itself.

Unfortunately, it means using gap-filled records or observations with errors and uncertainty can have a knock-on effect on the accuracy of the digital simulations. Added to this is the sheer amount of computational power needed to run large-scale simulations and observe natural phenomena at such focused scales. As the adoption of these technologies expands, we need to make sure we’re building sustainable data centres and developing information infrastructure responsibly.