This is the second article in a two-part series that examine best practices for evaluating performance incentive mechanisms (PIMs). The first article can be found here.

Performance incentive mechanisms (PIMs) are a versatile tool to incentivize utilities to achieve specific regulatory outcomes. PIMs can also be a powerful instrument to support affordability, particularly when designed to incentivize deployment of lower-cost resources that utilities otherwise might underinvest in, like energy efficiency. However, intentional and effective evaluation is needed to ensure that the benefits of PIMs outweigh the potential costs, especially during a stubborn affordability crisis.

Drawing on interviews with Northeast regulators and RMI’s experience reviewing PIMs in other regions, we identified opportunities to strengthen PIM evaluation approaches. Below, we offer four recommendations for PUCs to consider as they review the success of these regulatory tools in delivering the expected benefits for customers.

1. Evaluate PIMs on a recurring basis, and make the findings transparent

Some states do evaluate PIMs on a regular or standardized basis, typically within the course of a specific proceeding. For example, in New York, earnings adjustment mechanisms (EAMs) are evaluated within a utility’s rate case, and in many states, energy efficiency PIMs are evaluated as a part of annual reporting. However, individual cases or dockets may have redacted sections, limiting the ability of the public to view utility progress.

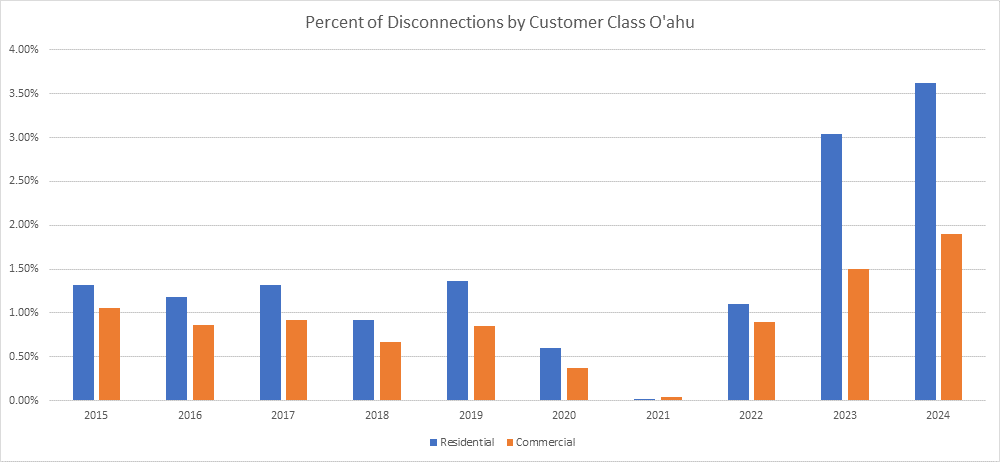

To remedy this challenge, some states have created interactive web-based dashboards of current and historical metrics (a specific, quantifiable measure used to assess a utility’s performance in achieving a desired outcome), scorecards (i.e., metrics with targets or benchmarks), and PIMs (metrics with targets and financial incentives). For example, Hawaiian Electric’s Performance Scorecards and Metrics page is designed to increase transparency and support the ability of regulators and stakeholders to evaluate performance. With better transparency on metrics and scorecards in addition to PIMs, regulators can better evaluate progress against important outcomes, which could inform policy development or future PIM design. One of the reported metrics displayed on the dashboard is a Disconnections Reported Metric. The Hawaii PUC used the information reported for that metric to assess the scale of disconnections in the state and launch a process to investigate potential disconnection reform.

Such dashboards are being considered in other states as well. In Connecticut, PURA plans to require the electric distribution companies to report their performance mechanism data through a transparent, accessible web dashboard. In North Carolina, Duke Energy reports on PIMs and metrics on their website on an annual basis.

Over time, these dashboards can grow to include utility performance against PIMs and the value of the resulting reward or penalty. In addition, states can take advantage of RMI’s PIMs Database to benchmark and compare PIM design and performance on a given “emergent” outcome, including topics like electrification, affordability, and new reliability metrics. Where data is publicly available, the database includes information on how utilities have performed relative to the target and metric and what they have earned for their performance.

2. Evaluate all of a utility’s PIMs together

A siloed approach to evaluating PIMs can make it difficult for regulators to see the combined effects of PIMs on key regulatory goals, risking duplication and wasted ratepayer funds. To avoid this unintended consequence, states can create intentional coordination mechanisms to harmonize incentives.

PUCs can structure a form or minimum filing requirement that is standardized across all PIMs and request updates in that form from utilities. That data could be used in siloed dockets or in a dedicated process before or within a rate case to gain insights into both whether individual PIMs are achieving their intended outcome and whether a utility’s entire PIM portfolio is net beneficial. It can also help stakeholders and regulators understand whether there are interactive effects among individual PIMs, which will foster more holistic evaluation. In addition, regulators can consider what additional metrics or reporting may be required to better evaluate PIMs. For example, the Hawaii Low-to-Moderate Income Energy Efficiency PIM requires a report on how the utility worked with the third-party energy efficiency administrator to achieve savings.

Internally, states can implement regular cross-training sessions, workshops, and improved communication channels for staff members working on different types of PIMs. One approach is for staff to create trackers that bring together relevant PIMs across a shared reward structure (such as potential basis points) to understand the total potential basis points (or other structure) the PIMs add up to. Design choices can also support such evaluation. New York state, for example, bounded the size of incentives to a maximum of 100 basis points from new incentives in its REV Track 2 Order; such a requirement could encourage staff or stakeholders to test the portfolio of metrics against that guidance. By tracking total PIMs across all dockets, states can track progress against such policies.

3. Create Opportunities for Informal Dialogue about PIM Development and Evaluation

PIM development and evaluation can be highly resource intensive for PUC staff. To reduce the administrative burden associated with these mechanisms, PUCs can set up informal, non-contested spaces for dialogue where stakeholders can support both the PUC’s PIM design and retrospective evaluation work. While such spaces will still require staff effort to ensure their outputs are useful, stakeholders may be able to guide the structure of cost-benefit analysis of PIMs, share insights into on-the-ground impacts of utility actions, or otherwise support information gathering beyond formal data requests.

Further, stakeholders may have unique perspectives on the outcomes being measured by a PIM that PUC staff might not otherwise surface in their evaluation of PIMs. For example, community-based organizations or consumer advocates may have insight into whether PIMs designed to expand customer affordability and equity actually helped customers. Distributed generation companies who directly interact with and benefit from well-run DER interconnection processes may have particular insight into DER interconnection PIMs, such as those in Hawaii, Illinois or New York.

Some states set up structured forums or advisory groups for specific PIMs, typically for design of PIMs, like Illinois’ informal workshops to support the development of performance and tracking metrics for electric utilities after the passage of the state’s Climate and Equitable Jobs Act. When successful, these more flexible forums can provide additional capacity for the PUC to educate stakeholders, bring in their ideas, and ensure that PIMs are effectively serving their purpose. These groups can also be re-convened when it comes time for evaluation to ensure that stakeholder perspectives are brought into the process of evaluating whether a PIM is achieving its intended outcomes.

4. Use guidance for PIM design to inform PIM evaluation

Our interviews and research found strong examples of design guidelines or principles for PIMs, such as in Rhode Island, Connecticut, and Illinois. Rather than create new guidance to support PIM evaluation, PUCs can re-use the same guidance to support their evaluation of whether the PIMs were effective in advancing desired outcomes.

PUCs can use that guidance or principles to outline a standard set of questions utilities can be prepared to answer — and evidence they should be prepared to provide — before renewal of PIMs into the next performance period. For example, one of the Rhode Island PIM principles states that “incentives should be designed to enable a comparison of the cost of achieving the target to the potential quantifiable and cash benefits.” This enables the PUC to ask utilities questions that clarify how the costs of achieving the target compare to the associated benefits. It also gives stakeholders a chance to comment on the utilities’ assessment of benefits, where they have insights into that analysis. If the PIMs don’t meet those standards, the PUC can consider whether to retire the PIM or modify it to better meet their expectations.

Similarly, Illinois state law requires that PIMs be evaluated based on their net benefits to customers. The statute directs the Illinois Commerce Commission to “develop a methodology to calculate net benefits that includes customer and societal costs and benefits and quantifies the effect on delivery rates.” This statutory requirement promotes a more structured and outcome-oriented evaluation framework — one that emphasizes measurable value to customers and the broader public. It also creates an opportunity for independent, transparent assessments of PIMs, helping to inform future incentive design and ensure that ongoing mechanisms are delivering real, quantifiable benefits.

Our research found that PUCs often focus evaluation efforts on those PIMs which obviously need attention or modification, but may not know whether other PIMs are clearly delivering benefits. An approach where the regulator evaluates all PIMs based on common design guidelines may reveal needed changes to maximize the value of these mechanisms.

Perfecting the PIMs Process

As states face affordability challenges and seek all options to contain costs, PIMs must be evaluated not just on intent, but also on actual outcomes. By evaluating PIMs on a recurring basis and creating mechanisms for transparency, assessing PIMs as a portfolio, and using the guidance from PIM design to inform evaluation, states can help ensure that these tools deliver net benefits to customers.

RMI’s PIMs Database offers one tool to support PUCs in exploring PIM design and performance for the growing set of emergent outcomes states are prioritizing. In addition, RMI can support PUCs to design agile processes that advance their efforts to tie utility incentives to their performance.

The post How PIM Evaluation Can Level Up appeared first on RMI.