Methane emissions are a global problem and a growing concern. Reducing emissions from dairy farms is a key piece of a bigger environmental picture as the livestock industry looks for ways to reduce the size of its greenhouse gas footprint.

According to a recently published study, Sulfate Additives Cut Methane Emissions More Effectively at LowerLiquid Manure Storage Temperatures, “the agricultural sector contributes to global methane emissions, and in Canada, approximately 29 percent of methane emissions were due to the agriculture sector.” The study was conducted by the Science and Technology Branch of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada.

Part of the problem is what’s known as “enteric methane,” a by-product of the natural digestive process that takes place in ruminant animals, like cattle, and is naturally expelled by these animals. The other major contributor is stored manure, and according to this study, the latter can be addressed, “at low capital cost and in the near term.”

The study explains that manure stored anaerobically in tanks or lagoons creates an environment in which microorganisms produce methane. Furthermore, the production of methane becomes a bigger issue in warmer weather. So, although methane production may not be an issue in the winter months, it is a major concern in the summer when temperatures rise.

According to this study, temperature and time play key roles in the production of methane. The higher the temperature, and the longer that temperature remains high, the larger the quantity of methane produced in the manure. Optimal temperatures for methane production are 25ºC and higher, and the study reports that as much as 87 percent of yearly methane emissions can occur in the span of only three warm months.

Sulfuric acid vs. calcium sulfate

While there may be a number of ways to reduce methane emissions from stored liquid manure, the study reports that additives are likely one of the most effective, since this approach is potentially scalable, affordable, and flexible enough to work for a variety of farm sizes.

One of these additives is sulfuric acid, which has been reported to significantly reduce methane emissions. However, according to the authors of this study, sulfuric acid presents potential health risks, which can only be mitigated with specialized training for handlers and careful storage. That’s why this study also looked at an alternative to sulfuric acid, namely calcium sulfate. Although not as effective, calcium sulfate “did show significant reductions in methane production when compared with the control.”

The study, conducted in a temperature-controlled environment, compared sulfuric acid and calcium sulfate to inhibit methane production at 18, 21 and 24ºC, representing summer manure temperatures on farms in different regions of Canada.

As expected, the experiment showed that methane production was highest at 24ºC, and lowest at 18ºC. “Temperature also plays a role in how often you need to apply the additive [sulfuric acid or calcium sulfate],” says Andrew VanderZaag, research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, and co-author of the study. “We’re trying to figure out what would be the right prescription in terms of how often you would need to reapply the additive in order to maintain a high level of efficacy over the warm season. We don’t have that information yet.”

What we do know, explains VanderZaag, is the warmer the weather, the more often farmers would have to reapply one of these additives. “So we know the direction, but we don’t know the exact details,” he says. “That’s what we would have to work out [by conducting this experiment] on a farm.”

Another reason testing these methane-reducing additives on an actual farm is a logical next step, he says, is because temperatures are kept at a constant level in a lab. In the real world, they fluctuate hour-to-hour and day-to-day.

One of the key findings of this study is that sulfuric acid is, as expected, more effective at reducing methane production than calcium sulfate. Moreover, sulfuric acid offers another benefit. “We didn’t address this in the study,” says VanderZaag, “but sulphuric acid reduces the pH [of the manure], which decreases the loss of ammonia into the air. So that’s a co-benefit, which you’re probably not going to see with calcium sulphate.”

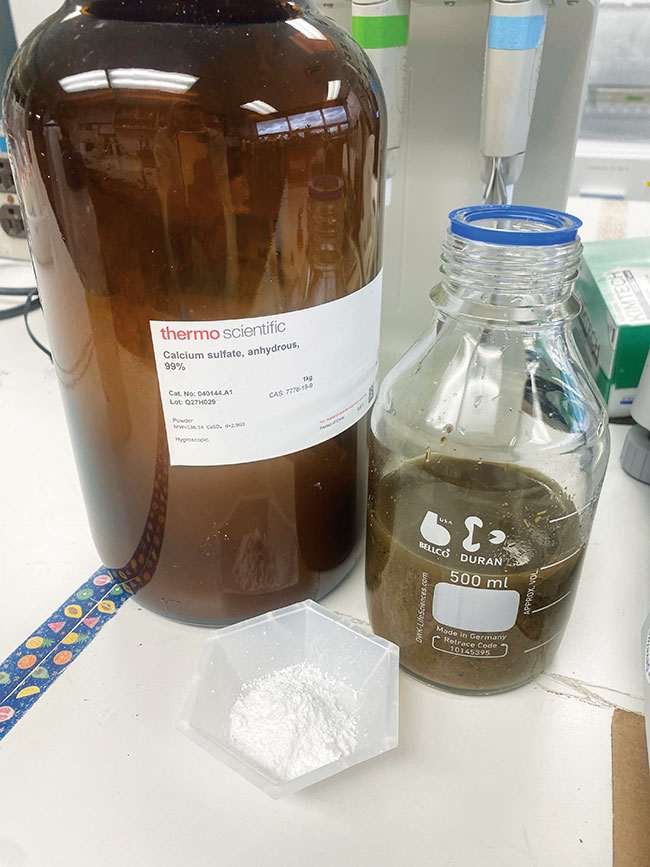

Lab gas calcium sulphate and manure used for AAFC’s comparative study of additives.

All images courtesy of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Affordable additives

While the study proved sulfuric acid and calcium sulfate can effectively cut methane emissions, farmers may wonder if this is cost-effective. “I think so,” says VanderZaag. “There’s an existing supply chain for fertilizer, and for certain industries sulphuric acid is a fertilizer. And gypsum is used for many things, like drywall, so there’s a supply chain there that can be tapped into.”

The question is how much sulfuric acid or calcium sulfate a farmer would need to have a meaningful impact on the amount of methane their stored manure generates? That number, unfortunately, is something that this study can’t conclusively determine.

There are variables, says VanderZaag. “First, you don’t need to treat manure year-round – only in the few summer months, and maybe early fall when the temperature in the manure is above the threshold of 15ºC.” VanderZaag specifies 15º because according to the study, “there is evidence to suggest that little methane is produced at or below 15ºC.”

Furthermore, he says in colder parts of the country, additives may only be needed for between two to four months because the manure won’t stay above the 15ºC threshold for longer periods of time.

The other variable that will impact the amount of additive is the quantity of manure they have in storage during the time of the year when manure temperatures would rise about the 15º threshold. “It’s the amount of manure in storage during the warm part of the year that matters. That’s what has to be treated,” says VanderZaag.

He explains this study looked at liquid manure, specifically, because solid manure isn’t a major concern, when it comes to methane emissions.

In addition, although the amount of methane that may be produced in manure from different animals, like swine or cattle could vary, “in general, there are a lot of similarities,” he says. “The biology and the methanogens that are actually producing the methane, are going to be there in both cases, so in broad strokes, I would say the two are similar.”

Solid manure, adds VanderZaag, is more complicated. “The greenhouse gas budget is partly from nitrous oxide, partly from ammonia and partly from methane,” he says. “You have to address them all together, otherwise if you decrease one, you increase another. With liquid manure, we can focus on just the methane.”

Translating lab findings

The findings in this study are based on adding roughly two grams of additive to a liter of manure. “That translates to about 2kg per cubic meter, or per ton of manure,” says VanderZaag. “It’s a similar rate for both sulfuric acid and calcium sulphate.”

Although this formula produced favorable results in a lab setting, VanderZaag admits we can’t be sure if this ratio would work at scale in a farm setting. “What we saw is that regardless of the temperature, we could get a 50-60 percent reduction [in methane] with calcium sulphate, and a 70-80 percent reduction with sulphuric acid.” That said, this was not a one-and-done approach, he explains. “We had to add more [sulfuric acid or calcium sulphate] after a period of time,” he says. “At 24º, we had to add it again after about a month, while at 18º the [methane reducing] effect could last several months.”

In other words, the lower the temperature, the less often either additive has to be mixed into the manure. “If the temperature is cooler, you don’t have to reapply very often,” he says. “You might only need to add it once for the warm season, whereas at a higher temperature, you might need a higher dose or a higher rate, but we don’t know that yet for sure.”

Next steps

While this study is encouraging, Vander-Zaag says replicating these results in the real world is a must to see how these additives will work on an actual farm, and to determine if the application is scalable.

“The full farm-scale study… is what we would like to do in the near future, and we’re applying for funding to do that.” •