When manure is applied to soil, the nutrients it contains don’t instantly become available to crops. Instead, a series of chemical, physical and biological processes unfold between application and nutrient uptake. Factors such as manure composition, site conditions, and weather all influence how quickly nutrients become available – or are lost to the environment. Soil microorganisms play a key role in this process, using carbon for energy and nitrogen for growth as they break down organic matter.

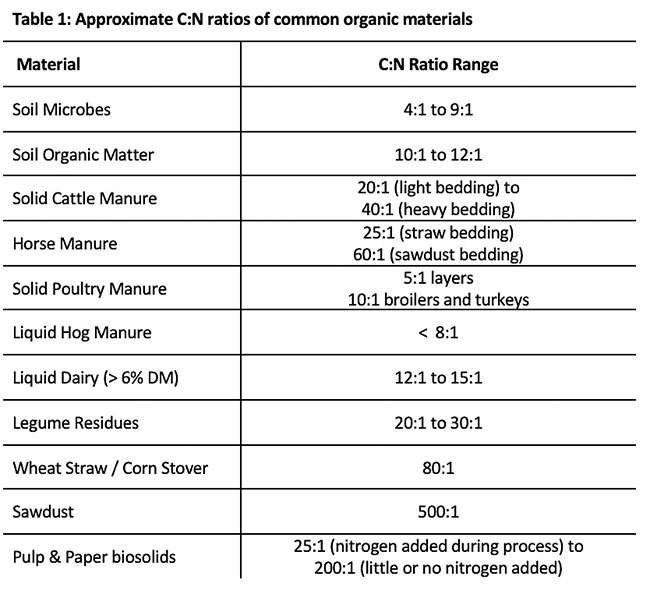

When manure is applied to a field, it adds both nutrients and organic matter to the soil. The carbon-to-nitrogen (C:N) ratio in a manure analysis indicates the proportion of organic carbon to total nitrogen in the material. Table 1 shows the approximate C:N ratio for common organic materials.

The typical soil C:N ratio is around 10:1, which represents a stable equilibrium that supports nutrient cycling. Soil microbes rely on this balance. When the C:N ratio of an amendment is higher than that of the soil, microbes will immobilize nitrogen – using it to break down excess carbon. This can temporarily reduce nitrogen availability to crops, potentially causing deficiencies. Conversely, if the C:N ratio is lower than that of the soil, decomposition occurs rapidly and nitrogen is mineralized, increasing its availability to plants.

Interpreting C:N ratios for nutrient management

An analysis that includes C:N ratio is effective since there is a wide range within and between livestock species. Generally,

- Liquid hog manure, with high N and low carbon has a C:N ratio ranging between 2:1 to 6:1, resulting in rapidly available N when soil microbial populations are active

- Liquid dairy manure (undiluted) will generally have a higher C:N ratio (around 12:1) due to forage-based rations. The higher the water content, the lower the C:N ratio.

- Horse manure with high bedding may exceed a C:N ratio of 50:1, leading to nitrogen immobilization unless supplemented.

- Poultry manure, often bedded with wood shavings, typically has a C:N ratio near soil equilibrium, making it a good source of readily available nitrogen.

- Pulp and paper biosolids can range from 25:1 to over 200:1. Without added nitrogen, their contribution to crop nutrition may take more than one growing season. Some processors add nitrogen to reduce C:N ratio to near 25:1, improving nutrient availability.

When heavily bedded manure with low nitrogen content is spring applied ahead of a nitrogen-demanding crop like corn, supplemental nitrogen may be necessary to avoid early-season deficiencies.

Why C:N Ratio matters in a manure analysis

Including the C:N ratio in a manure analysis helps predict:

- When nitrogen will become available

- Whether supplemental nitrogen is required

- How manure will interact with soil microbial activity

For example, solid cattle manure with a higher proportion of organic N and a higher C:N ratio may release more nitrogen when applied in the fall, allowing microbial breakdown to begin before soil temperatures drop below 10oC (50oF). In contrast, the same manure spring-appliedmay be slower to release nitrogen when crop needs are high due to cooler soil temperatures and slower microbial activity.

Even liquid cattle manure with C:N ratio close to soil equilibrium may not release nitrogen in sync with crop demand during a cool, wet spring – sometimes requiring additional commercial nitrogen to support early-mid-season growth. •