“As with the moon…a nutmeg has two hemispheres; when one is light, the other must be in darkness—for one to be seen by the human eye, the other must be hidden.”

Some books you can’t put down. The Nutmeg’s Curse by Amitav Ghosh isn’t one of them. Each chapter, often each page, leaves you reeling. The force of his logic is overwhelming, uncomfortable, and brilliant. It’s like spending your whole life staring at one side of the moon, only for Ghosh to turn it around and reveal that the other side looks nothing like you imagined. It demands not to be rushed; each idea needs time to settle, especially the ones that offer you a perspective that could completely reshape how you see the world.

If that sounds daunting, it shouldn’t. Reckoning with the forces that underpin ecological collapse is a small price to pay. Understanding these dynamics at scale and making them common knowledge is essential if we’re to shift towards a society that lives sustainably and within its means.

“Do not miss this book – and above all, do not tell yourself that you already know its contents, because you don’t” ~ Naomi Klein on The Nutmeg’s Curse

Power, Empire, and Ecological Breakdown

In The Nutmeg’s Curse, Ghosh powerfully argues that the environmental crisis we face is not just ecological; it is deeply political and moral. He traces its roots to Western colonial expansion, where extractive ideologies treated both nature and colonised peoples as resources to be dominated and consumed.

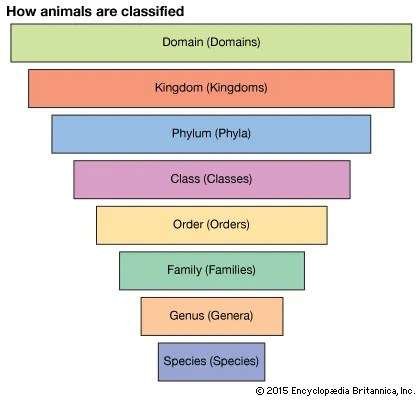

He demonstrates that these ideologies were systematically embedded through acts of genocide and ecocide, but also through more subtle mechanisms, such as the imposition of the Linnaean system of classification. “It was by… naming the environmental endowments of empires that… specialists made it possible for imperial policy-makers in Europe to decide how best to make use of these resources,” he writes. The Linnaean system enabled everything in the natural world to be named, compared, and ultimately reduced to its utility. In doing so, it helped “claim a monopoly on truth” by discounting Indigenous and non-Western ways of knowing.

But the book doesn’t just look to the past. Ghosh demonstrates how the same worldviews persist today and may well explain why we continue to harm the planet, even while fully aware of the consequences.

Take fossil fuel extraction. We can only justify continued drilling if we see the Earth as an inert storehouse of resources, rather than a living system we’re part of. As in the 18th century, power lies at the heart of this seemingly irrational behaviour.

In a world dependent on energy, those who control oil and gas wield immense geopolitical power. Unlike renewables, which can be produced almost anywhere, fossil fuels must be transported across oceans, through choke points that can be controlled. What’s more, buying oil or gas typically requires first purchasing US dollars, a legacy of the petrodollar system. In this way, control over energy becomes control over the world. Why else would the US continue to scale up extraction, while China pours investment into domestic infrastructure to generate energy on its own soil? As Ghosh writes, “One of the great blessings of renewable energy, from an ecological point of view, is that it does not need to be transported across oceans. But that aspect of its materiality is precisely its greatest shortcoming from a strategic point of view: renewable energy does not flow in a way that makes it vulnerable to maritime power.”

What We Forgot

Ghosh argues that by systematically “othering” nature; by treating it as separate from humanity and reducing it to an inanimate commodity, we have lost sight of its true essence. We have forgotten not only that we rely on it, but that it is a force itself. This force, Ghosh suggests, is not passive. It responds. The increasing frequency and intensity of natural disasters — wildfires, floods, droughts, hurricanes — can be read not as random events, but as the Earth’s backlash to centuries of abuse. “To look at the climate crisis through the lens of political violence,” he writes, “is to recognize that the Earth may be capable of executing its own version of what is known in the language of statecraft as ‘asymmetric warfare.’”

Yet even in the face of this reckoning, many of the world’s most powerful actors continue to operate under the illusion of immunity. The lifestyle of endless growth and consumption is not only unsustainable, it is self-destructive. As Ghosh puts it, “It is the ‘divine angel of discontent’ who metastasized cars into SUVs, and houses into McMansions.” Left unchecked, he warns, this discontent will consume the planet, and eventually, even those who believe themselves protected by wealth and power.

In stark terms, Ghosh argues that the climate crisis is not simply about what the planet can endure, but about what a particular way of life is willing to sacrifice to survive. “What is at issue is not ultimately what is sustainable for the planet,” he writes. “What is at stake is a way of life, founded on high consumption and defended by military power, that can only survive if large numbers of poor, low-emitting people are eliminated.”

To change course, Ghosh suggests, we must first remember. Our survival depends not only on technological solutions or political agreements, but on rekindling a relationship with nature built on respect, reciprocity, and humility. It is only through this reconnection with Earth as a living, responsive force that we might begin to imagine a different future.

Remembering Matters

In Robin Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass, she asks, “How can we begin to move towards ecological and cultural sustainability if we cannot even imagine what the path feels like? Our relationship with land cannot heal until we hear its stories. But who will tell them?”

In The Nutmeg’s Curse, Amitav Ghosh offers one such telling. He not only underscores the need to make space for Indigenous and non-Western ways of knowing, but also traces the story of how we came to forget. By exposing the historical forces that severed our connection to nature, he helps us see why remembering matters.

This book is for anyone who wants to understand the roots of our ecological crisis and what it will take to truly address it.

Be Curious

- After reading The Nutmeg’s Curse, read Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Kimmerer and This Changes Everything by Naomi Klein.

- Check out/follow The Decolonial Atlas, a growing collection of maps which are trying to ‘help us to challenge our relationships with the land, people, and state.’ I liked this one: ‘Interstate and International US Migrants’

- Watch the BBC’s Sacred Wonders docu-series, which highlights global Indigenous rituals and beliefs.

The post Reading This Book Could Change How You See the World appeared first on Curious Earth.