“Two years ago we were talking about the winter being over in the next summer, but it feels like we are entering the ice age,” observes Plantible cofounder Tony Martens in this year’s AgFunderNews festive vox pop. “M&A and exit pathways need to be established in order for the industry to come back alive.”

And vague platitudes about fixing the broken food system certainly won’t cut it in this environment, says Annick Verween at early-stage investor Biotope. Founders, she says, have to cut to the chase.

“Startups spend too much time framing the bigger problem. The fact that all of us want to have a better world does not need three slides. What we want to know is what is the pain that you are solving for your customers and who is willing to pay for your solution?”

Against this backdrop, we’ve highlighted nine areas to watch in 2026 spanning everything from proposed changes to the GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) process to insect ag, a segment that’s put out some mixed signals in 2025.

1 – Alt-protein recalibration

In the alt protein space, the answer to Verween’s two fundamental questions (what problem are you solving and who will pay for your solution?) remains frustratingly opaque for many companies.

Some have called it quits, some are pivoting to other industries, some are focusing on higher value segments, and some are going into hibernation mode. Others still have money in the bank and even modest growth, but no obvious path to delivering anything close to the returns needed to justify over-inflated valuations.

Beyond Meat, meanwhile, has restructured its debt, but arguably just kicked its debt problem down the road (the debt is now due in 2030, not 2027) unless Ethan Brown’s bid to “build a global protein company for tomorrow’” bears spectacular fruit in the next four years.

So where do we go from here?

In the short term, we can expect more consolidation, with IP and talent up for grabs as firms that can’t see a path forward under their own steam seek to salvage something from all that blood, sweat and tears.

Longer term, it’s unclear where the sector is headed. The problems it was designed to tackle have not gone away, and several startups have attracted significant funding rounds this year (Every Co, Formo, The Protein Brewery, Vivici, Better Meat Co, Revyve, MATR Foods, Heura).

And while some players in alt meat may be struggling, the relentless demand for protein—especially the kind that can replace eggs or enable formulators to add ever higher amounts to foods and beverages without compromising taste or texture in the age of Ozempic—shows no signs of abating.

All of which presents opportunities for players making everything from whey protein in fermentation tanks to new kids on the block such as guar protein.

As for the former, the business case has arguably become more compelling in the past year or two as animal-derived whey protein prices have increased, with demand exceeding supply, although the unit economics remain challenging.

As a result, several players in this “animal-free dairy” space have shifted their focus towards higher-value dairy proteins such as lactoferrin (All G) or osteopontin (Better Dairy), or found ways to add value via functionalizing whey proteins (Verley) or using casein micelles as a slow-release delivery system for key minerals (Eden Brew).

As for alt eggs, The EVERY Company, which pioneered the use of precision fermentation to make egg proteins with microbes instead of chickens, recently announced the first close of its $55 million Series D round and says products featuring its proteins are about to roll out across the US at Walmart.

“EVERY has crossed the line from promise to proof,” says Martin Davalos at McWin Capital Partners. “They’re not talking about proof-of-concept pilots here; they’re selling metric tons of product at scale to some of the biggest food companies on the planet.”

On a less positive note, EVERY is currently battling with fellow precision fermentation startup Onego Bio in an increasingly ugly dispute over IP, which we’ll be following in 2026.

👉 🎥 Agrifoodtech in 2025: What broke, what bent—and what might still work

👉 Foodtech IP fight escalates as The EVERY Company and Onego Bio trade accusations

👉 Perfect Day says Gujarat facility on track for 2026 start, 2027 ramp-up for recombinant whey protein

2 – Is it the end for self-GRAS affirmations?

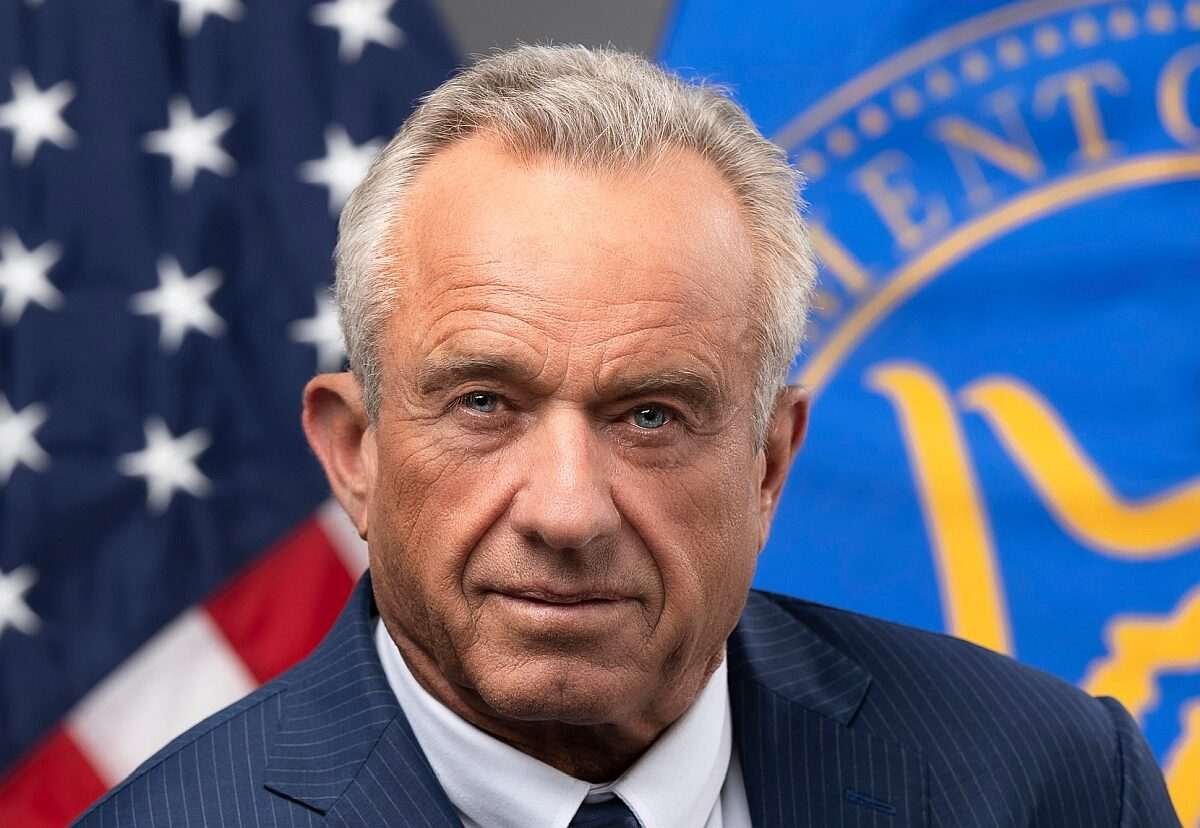

Another key area of concern for foodtech startups is RFK Jr’s proposal to axe the self-GRAS process, by which companies can self-affirm their products as safe following expert review, but do not have to get pre-market approval from the FDA.

While many stakeholders have concerns about this mechanism, axing it and requiring every ingredient currently self-affirmed as GRAS to submit a GRAS notification would create a massive regulatory bottleneck at an agency that has seen its headcount slashed in recent months, say critics, who believe the issue can be addressed without throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

As of December 1, 2025, FDA’s proposed GRAS reform rule is pending review by the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB), which signals that FDA could issue it in the coming weeks. However, questions have been raised about whether the FDA can require mandatory GRAS submissions without federal legislation that amends the FD&C Act’s food additive provisions, raising the possibility of a legal challenge.

👉 RFK Jr takes aim at self-GRAS process, but what does it mean in practice?

👉 Self-GRAS is flawed, says ANH-USA, but ditching it would ‘create a massive regulatory bottleneck’

3 – Nutrition in the age of Ozempic

It’s too early to say how GLP-1 drugs might shape the food industry, but few doubt they could have seismic effects should the next generation of products (which come in different formats and target more receptors) become better tolerated, more accessible, and more affordable.

In the short term, food manufacturers and retailers are still trying to navigate this space, with some developing companion products and digital tools for users and others attempting to find natural alternatives to Ozempic et al, although the jury is still out on their efficacy.

How this fits into the ultra-processed foods debate will be interesting to monitor. Could it fundamentally reshape the American diet by slashing demand for junk food and driving sales of fresh produce? Or is it just an opportunity for “Big Food” to design ever-more processed “solutions” to solve the problems it arguably helped to create?

👉🎥 Tufts MD on GLP-1 and the protein obsession: ‘I worry we might be missing the mark’

4 – Ultra-processed foods in the spotlight

On that note, the first wave of public comments responding to an FDA/USDA request for information (RFI) on defining “ultra-processed foods” highlights the challenge facing regulators tasked with nailing down a definition.

The agencies have not yet explained how the definition might be used. However, the RFI notes that a uniform definition would “allow for consistency in research and policy” in the wake of a flurry of definitions emerging from state legislatures, which range from vague definitions such as “industrial formulations of food substances never or rarely used in kitchens” to far more specific ones: “a food or beverage that contains at least one” of a list of 11 food additives.

Meanwhile, voluntary initiatives are also emerging, with high-profile brands including Amy’s Kitchen and Califia Farms working with the Non-UPF Project (led by Megan Westgate, founder of the Non GMO Project) to develop a third-party standard for non-ultra-processed foods verification

The best-known system for defining degrees of processing is the NOVA system—developed by Brazilian researchers in 2009—which groups products into four categories based on exposure to certain ingredients and industrial processing technologies.

However, critics have voiced concerns over the system’s lack of nuance, which would class whole-grain breakfast cereals with added vitamins, fortified soy milk, whey protein, tofu, and commercially produced whole-wheat sandwich bread in the same “ultra-processed” category as candy, soda, and cookies.

Stay tuned in 2026.

5 – MAHA, self-GRAS, Dietary Guidelines

As for Robert F. Kennedy Jr’s MAHA (Make America Healthy Again) movement, it’s fair to say it’s been a mixed bag.

Supporters appreciate the focus on ultra-processed foods (although defining them is a minefield) and cleaning up product labels, while critics say the movement is riddled with contradictions. Notably, commitments to improve hospital food have been made at the same time that the administration is taking money away from hospitals, while plans to prioritize “whole healthy foods” in nutrition assistance programs such as SNAP have been made at the same time that the administration is aggressively cutting funding to the scheme.

In May, the MAHA Commission released a report offering a “devastating critique of what American society has done to its kids,” says nutrition expert Prof. Marion Nestle. But the follow-up, which was supposed to offer concrete solutions, missed the mark, she claims.

“The MAHA movement is activist. Is its crowning achievement going to be getting color additives out of breakfast cereals and ice cream? Replacing high fructose corn syrup with cane sugar?

Meanwhile, given that RFK Jr’s recent actions around vaccines and other public health issues directly contradict expert advice, many industry stakeholders fear that the upcoming Dietary Guidelines for Americans will go against established science and erode the public’s trust, notes Civil Eats.

👉 ‘Stunning’ MAHA report draws praise and fury: Stated goals undermined by GOP policies, say experts

6 – Digitization and AI

Another area we’ll be following more closely next year is the ongoing use of AI to drive efficiency in every part of the food industry from R&D and product development to manufacturing and supply chain management.

At Rich Products Ventures, for example, managing director Dinsh Guzdar is “trying to figure out that intersection of AI within the food system where we can find real value. As one example, automation is a big area with AI and back of the house for restaurants where they have issues with labor constraints, so we’re leaning into that.

“We’re also looking at technologies on the retail side that can help streamline order processing. On manufacturing, we’re looking at everything from inventory management to predictive maintenance.

“In the supply chain there is potential [for AI to help] connect the restaurant or retailer to the distributor to the manufacturer, predict demand better, market better, and manage inventory better.”

At SOSV, Po Bronson notes that portco FloVision is using AI to help food processors measure yield, monitor quality, and improve labor performance in real time, while Calyx is using AI in hen houses to enable firms predict weight ahead of time to help planning.

Some startups we’re watching include BRAINR (manufacturing execution systems), First Bite (SaaS for CPGs targeting foodservice accounts), Lumi AI (data analysis), and Keychain (operating systems for CPG). [Disclosure: AgFunderNews’ parent company AgFunder is an investor in Lumi AI.]

👉 First Bite brings foodservice trade spending ‘out of the dark ages’ with digital rebates platform

👉 Keychain raises $30m Series B, launches AI-powered operating system for CPG

7 – Rubisco: ready for prime time?

One of the most abundant proteins on the planet with digestibility and functionality rivaling animal proteins such as egg and whey protein isolate, RuBisCO is found in every green leaf, from duckweed to sugar beet. Despite its ubiquity, however, it has not become the plant protein of choice for the food industry . . . yet.

But that could change in the next year or two, say some key players in this space including US-based Plantible (which is extracting the protein from duckweed), and New Zealand-based Leaft Foods (which extracts it from alfalfa). “Everybody knows RuBisCO is the utopia protein,” says Leaft CEO Ross Milne. “But the issue was always, can we actually find an economically viable way of isolating it in a desirable form? Well that’s what we’ve done.”

👉 The planet’s most abundant protein is ready for prime time, says Leaft Foods

👉 Aspyre Foods taps duckweed for casein and RuBisCO: ‘We’re maximizing the biomass value’

8 – Crunch time for cultivated meat

On paper, cultivated meat looks like a no-brainer. Unlike plant- or fungi-based options, it has the allure of “real” meat without the ethical and environmental baggage, coupled with the promise of food security, which is moving up the agenda in many countries due to supply chain disruptions.

In practice, however, there’s no playbook for biomanufacturing meat at scale, funding has begun to dry up, and the political environment has become increasingly hostile in key markets such as the US and parts of Europe.

GOOD Meat, the first company to commercialize cultivated meat, has not yet landed on a model for profitable production at large scale, while UPSIDE Foods has paused plans to build a large-scale facility in Glenview, Illinois, in favor of expanding its smaller “EPIC” site in California. Believer Meats and Meatable, meanwhile, have both ceased operations.

That said, from a purely technical perspective, significant progress has been made in recent years, claimed Lever VC in a recent white paper, although it acknowledged that it will be “many years if not decades before we’ll have a sense of how the sector as a whole will ultimately fare.”

There have been some positive announcements over the past year, meanwhile, with Sydney-based Vow securing regulatory approvals in Australia and New Zealand and proving its tech at 20,000-liter scale with positive margins and Dutch pioneer Mosa Meat securing a €15 million ($17.6 million) funding boost this month.

UK-based Meatly, which focuses on the petfood market, meanwhile, has developed a patent-pending low-cost bioreactor in-house and brought media costs down to 22p/liter, a number CEO Owen Ensor claims could get down to just 2p/L with economies of scale.

👉 Mosa Meat raises $17.6m; prioritizes ‘fundamentals over speed’

👉 What went wrong at Believer Meats? Sources point to risk, scale, and timing

9 – Insect ag reckoning

The signals coming from the insect ag space have been mixed this year, with some high-profile business failures coupled with funding rounds from new players.

Danish insect ag co ENORM was declared bankrupt, South African BSFL startup Inseco ceased operations, and French mealworm farmer Ÿnsect went into judicial liquidation.

In May, receivers were called in to Canada-based cricket farmer Aspire Food Group by lender Farm Credit Canada when it became clear the firm could not meet its financial obligations. The Ontario Superior Court of Justice later approved a deal to sell the assets to Halali Group Holdings.

However, new players are still attracting funding, with nextProtein securing €18 million ($21 million) last month to scale production in Tunisia and Volare bagging €26 million ($30 million) in May to scale production in Finland.

Meanwhile, French insect ag firm Innovafeed insists plans to build a commercial scale BSFL facility at an ADM corn milling site in the US “remain very much alive,” while Full Circle Biotechnology is building a 7,000-ton/year insect protein facility near Bangkok and Canadian startup Oberland Agriscience is scaling up to meet growing demand.

Finally, one company to watch is Nutriearth, a French startup scaling light-activated vitamin D3 from an intriguing new source: mealworms.

👉 Judicial liquidation for Ÿnsect as insect farming sector ‘struggles to become competitive’

👉 Exclusive: Aspire Food Group’s Ontario cricket farm sold to new owner as firm collapses under debt

And finally….

One story we’ll be keeping an eye on in 2026 is the legal battle between fast-growing protein bar maker David Protein and a clutch of smaller firms.

The dispute began earlier this year after David Protein acquired a foodtech firm called Epogee, which makes an ingredient called EPG that looks and functions like fat, with a fraction of the calories.

Three Epogee customers who claim that they built their business around EPG only to abruptly lose access filed a lawsuit accusing David of excluding competitors and creating an artificial monopoly.

Several other food companies have since supplied signed sworn statements outlining the harm they also claim to have suffered after losing access to the ingredient.

David Protein, however, says it is under no obligation to keep selling EPG to firms that have not signed long-term supply contracts and says formulators can choose from an “abundance” of alternatives.

👉 EPG showdown: Startups warn of ‘imminent permanent closure’ in fight with David Protein

The post Foodtech at a crossroads: recalibration, regulation, and harsh reality appeared first on AgFunderNews.