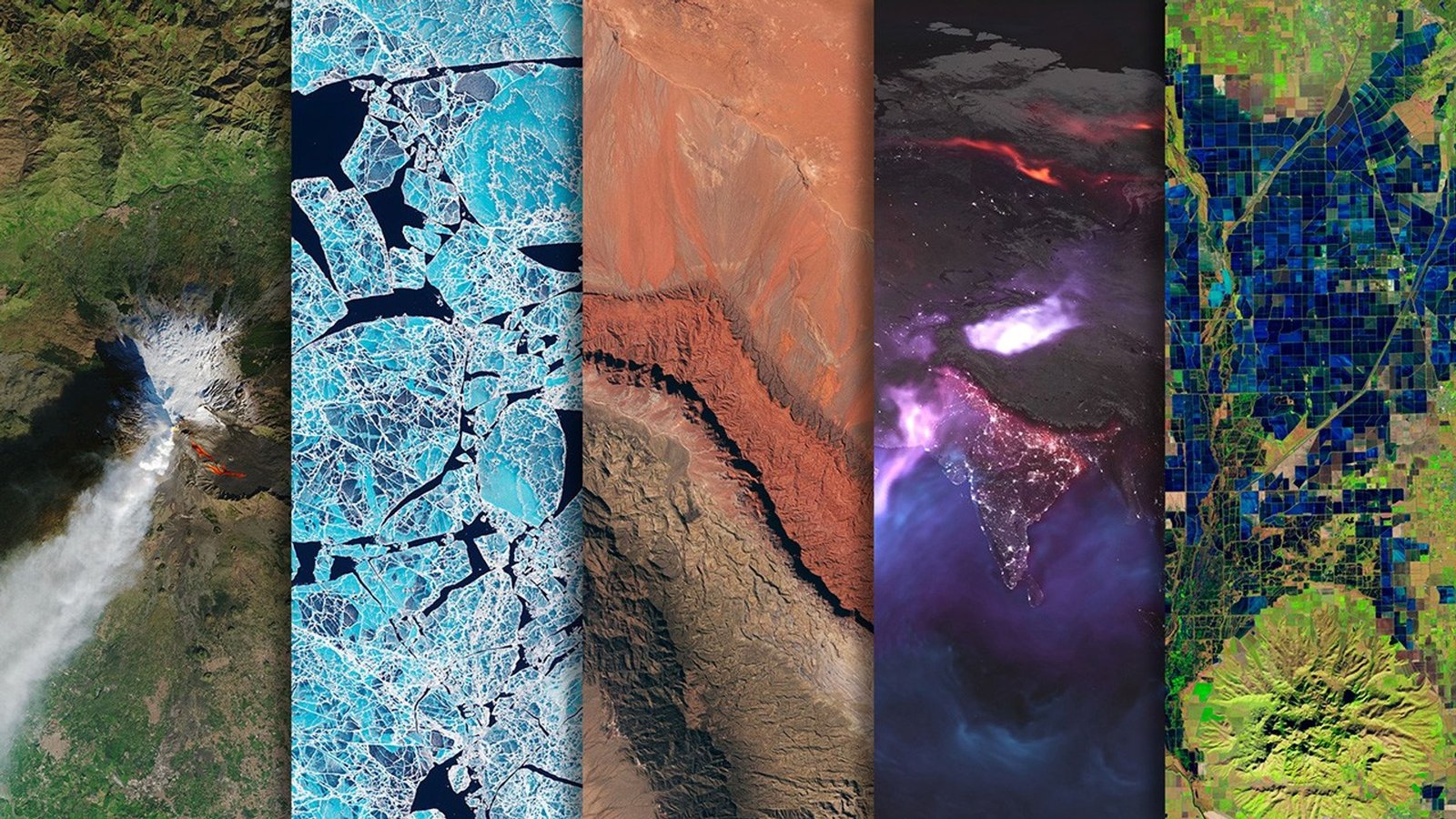

Icons of winter are sometimes found in unexpected places. In one striking example, a series of oval lagoons in a remote part of Siberia forms the shape of a towering snowman when viewed from above.

This image, centered on the remote village of Billings and nearby Cape Billings on Russia’s Chukchi Peninsula, was captured by the OLI (Operational Land Imager) aboard Landsat 8 on June 16, 2025. Established in the 1930s as a port and supply point for the Soviet Union, the village sits on a narrow sandspit that separates the Arctic Ocean from a series of connected coastal inshore lagoons.

The elongated, oval lagoons are frozen over and flanked by sea ice. Though June is one of the warmest months in Billings, ice cover is routine even then. Mean daily minimum temperatures are just minus 0.6 degrees Celsius (30.9 degrees Fahrenheit) in June, according to meteorological data.

Though the shape may seem engineered, it is natural and the product of geological processes common in the far north. The ground in this part of Siberia is frozen most of the year and pockmarked with spear-shaped ice wedges buried under the surface. Summer melting causes overlying soil to slump, leaving shallow depressions that fill with meltwater and form thermokarst lakes. Once created, consistency in the direction of the winds and waves likely aligned and elongated the lakes into the shapes seen in the image. The thin ridges separating the lakes may represent the edges of different ice wedges below the surface.

The first reference to humans building snowmen dates back to the Middle Ages, according to the book The History of the Snowman. While three spherical segments are the most common form, other variants dominate in certain areas. In Japan, snowmen typically have just two segments and are rarely given arms. This five-segmented snowman-shaped series of lakes spans about 22 kilometers (14 miles) from top to bottom, making it roughly 600 times longer than the actual snowwoman that held the Guinness record for being the world’s tallest snowperson in 2025.

Snowmen are not the only winter icons tied to this remote landscape. For early expeditions to the Russian Arctic, reindeer offered one of the most reliable modes of transportation. That includes expeditions by the town’s namesake, Commodore Joseph Billings, a British-born naval officer who enlisted in the Russian navy and led a surveying expedition to find a Northeast Passage between 1790 and 1794.

Although the hundred-plus members of the expedition did not reach Cape Billings, they explored much of the Chukchi Peninsula, producing some of the first accurate maps and further confirming that Asia and North America were separated by a strait. In the winter months, when their ships were beset by ice, the explorers moved to temporary camps on land and instead surveyed the region with reindeer-drawn wooden sleds, according to historical accounts. Winters, in fact, offered the best conditions for exploration because the peninsula’s many rivers and lakes turned into solid surfaces that were easy to traverse in comparison to the muddy bogs that open up in the summer.

Indigenous Chukchi people living on the peninsula at the time routinely used reindeer to haul both people and cargo. A pair of reindeer can comfortably haul hundreds of pounds for several hours a day. In addition to their impressive endurance in cold temperatures, reindeer largely feed themselves by digging through snow and grazing on lichens, something that neither sled dogs nor horses can do.

Historical documents indicate that the Billings expedition enlisted Chukchi people to manage and care for the reindeer they used, with some accounts suggesting that the explorers used dozens of reindeer at times. While reindeer were mainly used to haul sleds, Chukchi people likely rode them as well.

Non-Chukchi members of the expedition reportedly experimented with riding reindeer, though their experiments did not always go smoothly. Billings’ secretary and translator Martin Sauer reported using a saddle without stirrups or a bridle and falling “nearly 20 times” after about three hours of travel in his account of the expedition. Not only that, he added, but the saddle “at first, causes astonishing pain to the thighs.”

NASA Earth Observatory image by Michala Garrison, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Adam Voiland.

References & Resources

- Alekseev, A.I. (1966) Joseph Billings. The Geographical Journal, 132(2), 233-238.

- Arctic Portal Chukchi. Accessed December 16, 2025.

- Astronomy (2019, January 2) Ultima Thule emerges as contact binary, “cosmic snowman,” in new spacecraft images. Accessed December 16, 2025.

- Chlenov, M. (2006) The “Uelenski Language” and its Position Among Native Languages of the Chukchi Peninsula. Alaska Journal of Anthropology, 4(1-2), 74-91.

- Dokuchaev, A., et al. (2022) The First Scientific Expeditions to the Bering Strait and to the Russian Colonies in America. Arctic and North, 48, 179-208.

- Eckstein, B., via Internet Archive (2007) The history of the snowman. Simon & Schuster: New York. Accessed December 16, 2025.

- Hobden, H. Yakutia in the 18th century – The Great Scientific Expeditions – Part Two. Accessed December 16, 2025.

- Klokov, K.B. (2023) Geographical variability and cultural diversity of reindeer pastoralism in northern Russia: delimitation of areas with different types of reindeer husbandry. Pastoralism, 13, 15.

- Krylenko, V. (2017) Estuaries and Lagoons of the Russian Arctic Seas. Estuaries of the World, Springer: Cham, 13-15.

- NASA (2012) Views of the Snowman. Accessed December 16, 2025.

- Obscure Histories (2022, December 20) The Snowman: A brief history of a winter entertainment. Accessed December 16, 2025.

- Radio Free Europe (2015, March 10) The Village At The End Of The Earth. Accessed December 16, 2025.

- Sauer, M., via Internet Archive (1802) An account of a geographical and astronomical expedition to the northern parts of Russia. Strahan: London. Accessed December 16, 2025.

- Zonn, I., et al. (2016) Shores of the Chukchi Sea. The Eastern Arctic Seas Encyclopedia, 298-301.

You may also be interested in:

Stay up-to-date with the latest content from NASA as we explore the universe and discover more about our home planet.

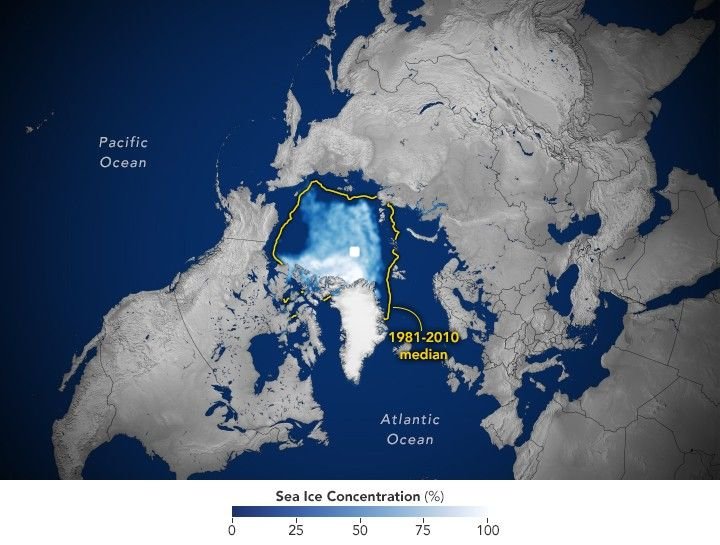

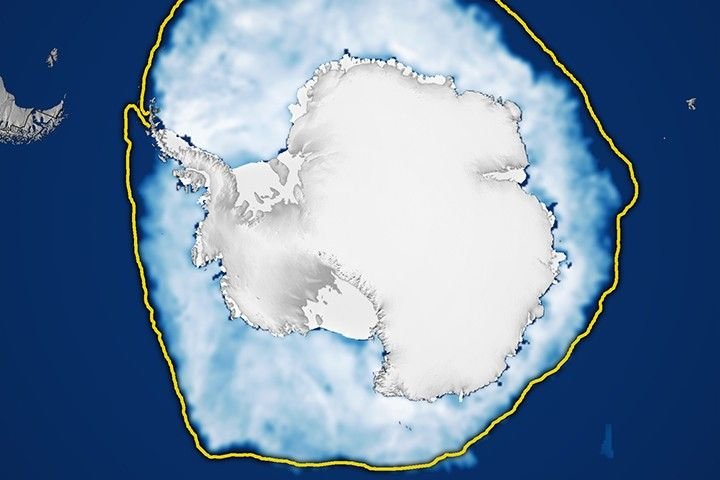

Satellite data show that Arctic sea ice likely reached its annual minimum extent on September 10, 2025.

Sea ice around the southernmost continent hit one of its lowest seasonal highs since the start of the satellite record.

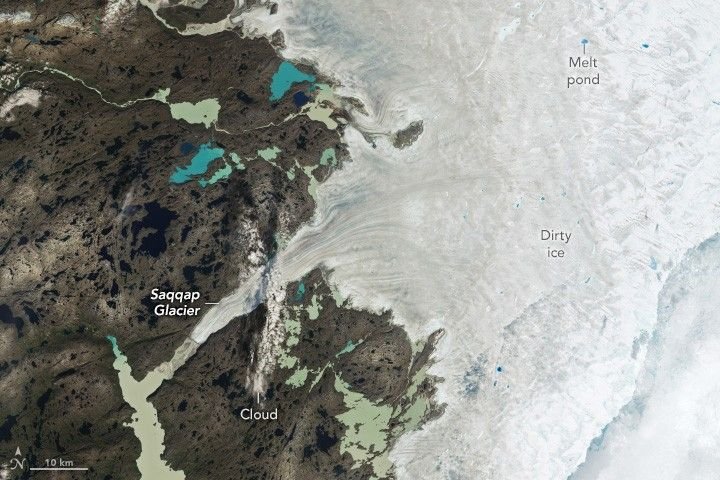

A moderately intense season of surface melting left part of the ice sheet dirty gray in summer 2025, but snowfall…